The SR-71 was designed for flight at over Mach 3 with a flight crew of two in tandem cockpits, with the pilot in the forward cockpit and the reconnaissance systems officer operating the surveillance systems and equipment from the rear cockpit, and directing navigation on the mission flight path.[27][28] The SR-71 was designed to minimize its radar cross-section, an early attempt at stealth design.[29] Finished aircraft were painted a dark blue, almost black, to increase the emission of internal heat and to act as camouflage against the night sky. The dark color led to the aircraft's nickname "Blackbird". While the SR-71 carried radar countermeasures to evade interception efforts, its greatest protection was its combination of high altitude and very high speed, which made it almost invulnerable. Along with its low radar cross-section, these qualities gave a very short time for an enemy surface-to-air missile (SAM) site to acquire and track the aircraft on radar. By the time the SAM site could track the SR-71, it was often too late to launch a SAM, and the SR-71 would be out of range before the SAM could catch up to it. If the SAM site could track the SR-71 and fire a SAM in time, the SAM would expend nearly all of the delta-v of its boost and sustainer phases just reaching the SR-71's altitude; at this point, out of thrust, it could do little more than follow its ballistic arc. Merely accelerating would typically be enough for an SR-71 to evade a SAM;[7] changes by the pilots in the SR-71's speed, altitude, and heading were also often enough to spoil any radar lock on the plane by SAM sites or enemy fighters.[28] At sustained speeds of more than Mach 3.2, the plane was faster than the Soviet Union's fastest interceptor, the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25,[N 4] which also could not reach the SR-71's altitude.[30] During its service life, no SR-71 was ever shot down.[8]

On most aircraft, the use of titanium was limited by the costs involved; it was generally used only in components exposed to the highest temperatures, such as exhaust fairings and the leading edges of wings. On the SR-71, titanium was used for 85% of the structure, with much of the rest being polymer composite materials.[31] To control costs, Lockheed used a more easily worked titanium alloy which softened at a lower temperature.[N 5] The challenges posed led Lockheed to develop new fabrication methods, which have since been used in the manufacture of other aircraft. Lockheed found that washing welded titanium requires distilled water, as the chlorine present in tap water is corrosive; cadmium-plated tools could not be used, as they also caused corrosion.[32] Metallurgical contamination was another problem; at one point, 80% of the delivered titanium for manufacture was rejected on these grounds.[33][34] The high temperatures generated in flight required special design and operating techniques. Major sections of the skin of the inboard wings were corrugated, not smooth. Aerodynamicists initially opposed the concept, disparagingly referring to the aircraft as a Mach 3 variant of the 1920s-era Ford Trimotor, which was known for its corrugated aluminum skin.[35] But high heat would have caused a smooth skin to split or curl, whereas the corrugated skin could expand vertically and horizontally and had increased longitudinal strength. Fuselage panels were manufactured to fit only loosely with the aircraft on the ground. Proper alignment was achieved as the airframe heated up, with thermal expansion of several inches.[36] Because of this, and the lack of a fuel-sealing system that could handle the airframe's expansion at extreme temperatures, the aircraft leaked JP-7 fuel on the ground prior to takeoff,[37] annoying ground crews.[21] The outer windscreen of the cockpit was made of quartz and was fused ultrasonically to the titanium frame.[38] The temperature of the exterior of the windscreen reached 600 °F (316 °C) during a mission.[39] Cooling was carried out by cycling fuel behind the titanium surfaces in the chines. On landing, the canopy temperature was more than 572 °F (300 °C).[35] Some SR-71s had red lines painted on the upper surface of the wing to show "no step" areas which included the trailing edge and the thin, fragile skin where the inner wing blended into the fuselage. This portion of the skin was only supported by widely spaced structural ribs.[40] The Blackbird's tires, manufactured by B.F. Goodrich, contained aluminum and were inflated with nitrogen. They cost $2,300 each and generally required replacing within 20 missions. The Blackbird landed at more than 170 knots (200 mph; 310 km/h) and deployed a drag parachute to reduce landing roll and brake and tire wear.[41]

The second operational aircraft[43] designed around a stealth aircraft shape and materials, following the Lockheed A-12,[43] the SR-71 had several features designed to reduce its radar signature. The SR-71 had a radar cross-section (RCS) around 110 sq ft (10 m2).[44] Drawing on early studies in radar stealth technology, which indicated that a shape with flattened, tapering sides would reflect most energy away from a radar beam's place of origin, engineers added chines and canted the vertical control surfaces inward. Special radar-absorbing materials were incorporated into sawtooth-shaped sections of the aircraft's skin. Cesium-based fuel additives were used to somewhat reduce the visibility of exhaust plumes to radar, although exhaust streams remained quite apparent. Johnson later conceded that Soviet radar technology advanced faster than the stealth technology employed against it.[45] The SR-71 featured chines, a pair of sharp edges leading aft from either side of the nose along the fuselage. These were not a feature on the early A-3 design; Frank Rodgers, a doctor at the Scientific Engineering Institute, a CIA front organization, discovered that a cross-section of a sphere had a greatly reduced radar reflection, and adapted a cylindrical-shaped fuselage by stretching out the sides of the fuselage.[46] After the advisory panel provisionally selected Convair's FISH design over the A-3 on the basis of RCS, Lockheed adopted chines for its A-4 through A-6 designs.[47] Aerodynamicists discovered that the chines generated powerful vortices and created additional lift, leading to unexpected aerodynamic performance improvements.[48] The angle of incidence of the delta wings could be reduced for greater stability and less drag at high speeds, allowing more weight to be carried, such as fuel. Landing speeds were also reduced, as the chines' vortices created turbulent flow over the wings at high angles of attack, making it harder to stall. The chines also acted like leading-edge extensions, which increase the agility of fighters such as the F-5, F-16, F/A-18, MiG-29, and Su-27. The addition of chines also allowed the removal of the planned canard foreplanes.[N 6][49][50]

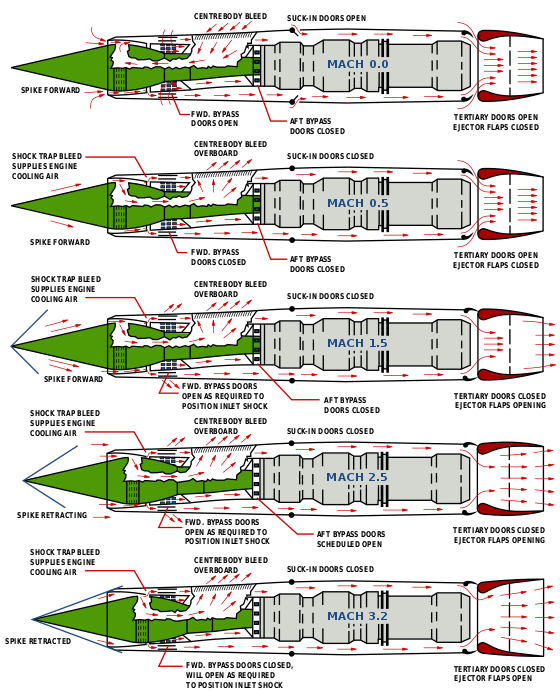

The air inlets allowed the SR-71 to cruise at over Mach 3.2, with the air slowing down to subsonic speed as it entered the engine. Mach 3.2 was the design point for the aircraft, its most efficient speed.[35] However, in practice the SR-71 was sometimes more efficient at even faster speeds—depending on the outside air temperature—as measured by pounds of fuel burned per nautical mile traveled. During one mission, SR-71 pilot Brian Shul flew faster than usual to avoid multiple interception attempts; afterward, it was discovered that this had reduced fuel consumption.[51] At the front of each inlet, a pointed, movable inlet cone called a "spike" was locked in its full forward position on the ground and during subsonic flight. When the aircraft accelerated past Mach 1.6, an internal jackscrew moved the spike up to 26 in (66 cm) inwards,[52] directed by an analog air inlet computer that took into account pitot-static system, pitch, roll, yaw, and angle of attack. Moving the spike tip drew the shock wave riding on it closer to the inlet cowling until it touched just slightly inside the cowling lip. This position reflected the spike shock wave repeatedly between the spike center body and the inlet inner cowl sides, and minimized airflow spillage which is the cause of spillage drag. The air slowed supersonically with a final plane shock wave at entry to the subsonic diffuser.[53] Downstream of this normal shock, the air became subsonic. It decelerated further in the divergent duct to give the required speed at entry to the compressor. Capture of the plane's shock wave within the inlet is called "starting the inlet". Bleed tubes and bypass doors were designed into the inlet and engine nacelles to handle some of this pressure and to position the final shock to allow the inlet to remain "started". In the early years of operation, the analog computers would not always keep up with rapidly changing flight environmental inputs. If internal pressures became too great and the spike was incorrectly positioned, the shock wave would suddenly blow out the front of the inlet, called an "inlet unstart". During unstarts, afterburner extinctions were common. The remaining engine's asymmetrical thrust would cause the aircraft to yaw violently to one side. SAS, autopilot, and manual control inputs would fight the yawing, but often the extreme off-angle would reduce airflow in the opposite engine and stimulate "sympathetic stalls". This generated a rapid counter-yawing, often coupled with loud "banging" noises, and a rough ride during which crews' helmets would sometimes strike their cockpit canopies.[54] One response to a single unstart was unstarting both inlets to prevent yawing, then restarting them both.[55] After wind tunnel testing and computer modeling by NASA Dryden test center,[56] Lockheed installed an electronic control to detect unstart conditions and perform this reset action without pilot intervention.[57] During troubleshooting of the unstart issue, NASA also discovered the vortices from the nose chines were entering the engine and interfering with engine efficiency. NASA developed a computer to control the engine bypass doors which countered this issue and improved efficiency. Beginning in 1980, the analog inlet control system was replaced by a digital system, Digital Automatic Flight and Inlet Control System (DAFICS),[58] which reduced unstart instances.[59]